Structural Anachronism: Chowdhury and Evers Put Time at the Centre of IR Theory in New Article

Bhaso Ndzendze

12 November 2025

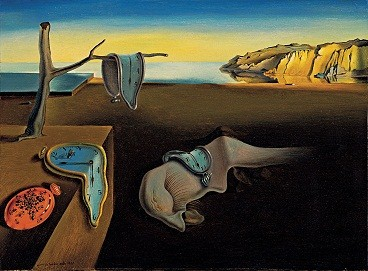

The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali (1931). Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

Lately I have been confronted with the thought that International Relations (IR) theory is essentially interpretive history, the thematic telling of history, based on the writer’s analysis of the most important trends of their subject. By aspiring to produce generalizable accounts of state behavior, IR scholars participate in the same effort. This is why political science – of which IR is a specialization – may be considered the final draft of history. But in their focus on the major themes, scholars (particularly those working within the Realist paradigm) have tended to focus on the most impactful actors – these tending to be the most powerful states. In so doing, they neglect the smaller states, which constitute the majority of the world.

But does resolving that problem pose a new one?

In a brilliant new article in the European Journal of International Relations (6 November 2025), Arjun Chowdhury (University of British Columbia, Canada) and Miles M. Evers (University of Connecticut, US) titled ‘Anachronism and International Relations theory‘ confront the problem of history and time in a unique problem of modern IR theory; the well-intentioned tendency to superimpose contemporary outlooks and concepts in bygone eras in an attempt to broaden geographical and historical representation (truly global history, and not just those of North America and Western Europe).

Making use of historical methods, archival sciences, and the philosophy of history, they argue that “two retrospective processes—information-destroying, which shapes what is preserved, and information-obscuring, which governs how that information is organized—flatten ideational variation in the historical record and distort the evidentiary foundations on which scholars depend for testing and building theories of world politics.” They term this structural anachronism.

Some examples they cite include studies of war such as Miller and Bakar’s (2023) conflict-event dataset, Kang’s

(2010) account of the Confucian long peace, and Phillips’ (2021) analysis of imperial diversity regimes, which, they assert, “draw on selective sources that elevate some conflicts over others and use ideal types that impose coherence on episodes.” They also critique accounts of order such as Butcher and Griffiths (2017) on precolonial systems, Spruyt (2020) on regional worldviews, and Zarakol (2022) on Chinggisid sovereignty, whom they find to “rely on retrospective sources that reframe political diversity through modern traditions and categories like sovereignty.”

Is the problem of structural anarchism better than the alternative? I think it is. Given that the other problem is essentially erasure, the potentially inaccurate representation of non-Western pasts in modern IR theory can be surmountable by incremental correction. Indeed it can only come into the fore of IR theory in that way, much as ever-new theories have emerged by being correctives to prior efforts. The authors themselves argue as much, acknowledging that all of historical writing is bound to participate in some level of structural anachronism.